Gilda, and Frogs and well, you'll just have to read the rest, oh my

What a performance with German Regie concept Opera taught me about resilience

In 2008, after a spellbinding morning gazing at the ancient Dardanelles, their shimmering waters framed by minarets piercing the sky, I stepped off a lavish ten-day opera cruise that had taken me from the sun-drenched ruins of Athens to the storied grandeur of Istanbul.

My destination?

Not some leisurely retreat, but the stage of the legendary Deutsche Oper Berlin, where I was about to open the season as Gilda in Rigoletto. For a small-town Southern girl—this was more than just a performance. It was a proving ground, a moment to stake my claim in the elite world of European opera. The weight of history, ambition, and the unknown pressed against me, but I was ready.

Or, so I thought.

Even though this was the grand season opener, the production itself was a relic from the 1980s—an old warhorse the company dusted off and revived from time to time. Revivals, however, come with a catch: minimal rehearsal time. We had just three days—three breathless, frantic days—to piece together an entire Rigoletto.

To put that into perspective, even in the budget-conscious world of American opera, the bare minimum for staging a production is two full weeks, plus a dress rehearsal week, making three weeks the accepted standard. And even then, a single newcomer to the opera or production could throw everything into chaos. Fortunately, I wasn’t that weak link. Having performed Rigoletto twice before, I knew this role inside and out, and despite the breakneck pace, I was certain it was the perfect choice for my German debut.

On the first day of rehearsal, we gathered with the production staff in the hushed corridors of the Deutsche Oper. Summer was drawing to a close, and the building felt strangely abandoned—most of the company was still away on vacation, leaving an eerie stillness in their absence. The emptiness intrigued me, stirring my recent obsession with Berlin’s World War II history. It was as if the air still held echoes of the past, a spectral weight pressing against the walls. I half-expected that if I dared to push open one of the heavy wooden doors, I’d find a striking yet severe blonde woman, impeccably dressed in a crisp military-style outfit, seated behind an imposing tanker desk, typing feverishly—her fingers hammering out the opera rehearsal schedules with the same relentless precision that once dictated the pulse of an empire. Kind of like a scene from Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

As we started on our first day, a German assistant stage director began giving us the logistics of our whirlwind three-day production build, her tone measured and pickled with the task's urgency ahead. When she uttered the name of the original production designer and director—Hans Neuenfels—it was with a near-religious reverence. Though I had only recently come across his name, it was instantly clear that in Berlin, Neuenfels was not merely respected but revered, a theatrical genius whose vision was to be upheld like sacred text. I felt a flicker of pride —I had been chosen to help resurrect his Rigoletto, an honor not lost on me. But just as I indulged in the quiet satisfaction of my own artistic validation, the assistant director, without so much as a shift in tone, glanced up from her five-inch-thick production binder and announced matter-of-factly, “Oh, and in this production, Gilda, you’ll be black.”

“Excuse me?” I stuttered. I was sure something had been lost in translation.

“Ja. Natürlich”, she said.

“This production was premiered with Harolyn Blackwell as Gilda. She is black, and Maestro Neuenfels worked her blackness into the production because the Rigoletto was white, and they couldn’t have been related. It is a very important point. There are themes throughout the production where we are trying to determine if Rigoletto captured her or is taking care of her. Is he really her father? Is he so innocent? Just go with it. It will all make sense as we go.”

With level 5 fire alarms blazing in my Georgia Southern Belle brain, I asked, “Shouldn’t you just cast black Gilda’s?”

Unfazed, shoulders back and determined, she continued to explain the rest of the production without a blip in the time continuum.

My management had mentioned that German regie theater could be eccentric and controversial and that blackface, sex, and all other sorts of wild happenings unheard of in American opera theaters took place in Europe. They had freedom from big donors and could use the operatic platform as commentary on any political or cultural subject and did so frequently. It was expected. Art served as their right as people who pursue it to aid in the definition of their humanness, albeit not always void of controversy.

Some German Regie theater is what I imagine a hallucinogenic trip through an opera house might feel like. First, reality is shattered into a billion jagged, kaleidoscopic fragments, each darker and more disjointed than the last, as if the sheer act of destruction is the point. Then, just when you think some logic might emerge, the director—gleefully reveling in the chaos—attempts to stitch it all back together into a so-called “cohesive” vision. Only there’s no stitching, no through line, just an explosion of wild concepts, avant-garde abstractions, and explanations so convoluted they make sense only to the fevered mind that dreamed them up. And yet, somehow, this dizzying spectacle is called art. The Germans love it.

“No hero’s journey predictability here,” I thought.

Like cattle, I went along for the trail ride.

Quickly, we began our stagings, which in this case was paint-by-number stage placement. The assistant director had a book with a drawing of the set that looked like a football playbook, and she gave us the exact moments in the music during which we were to do our actions. There was very little time to explain why the character would make a choice; actually, no time was spent on this. Once we had the map, we would then run a portion with music. The music was being conducted by someone on staff at the Deutsche Oper, and he was very excited to be a part of this production since it would be his first time performing the opera.

“Cool”, I thought. “An up-and-coming conductor for my debut here. He must be great. It will be nice to connect with someone just starting out, kind of like me.”

The staging continued, and most of it was a blur. In the stage manager’s defense, she was taking on a monumental task, and because the chorus knew the staging and the production staff knew the show so well, she was leaving out a lot of the connective tissue. We moved to cues in the text, but often, they didn’t make sense with what other characters were doing or experiencing on stage. Don’t even get me started about how the text did not matter. It was like we were all in our different worlds, and responding to what someone was saying wasn’t natural on this particular planet.

I was overwhelmed and thankful that I had done the opera before and understood my intentions for the text. But all of that started going out the window when she explained that during the duet with Rigoletto, I would be standing on a separate stage wagon that “looks the color of sand, with a palm tree. Be there for when you are to sing Quanto affetto so that you can meet the midget nun.”

“What?”

I was sure I misheard.

With a grin, she said, “Gilda is most likely not his daughter, and the midget nun will come and, during this scene, make the pact for your protection with you. It will be a child in a nun costume. Not a real midget.”

She sounded disappointed.

“They will have a large rubber finger coming out of the costume, and on this word, you will push the hand away from you. It is important! ON THIS WORD “Lassù in cielo,” or the child doesn’t know when to leave the stage!"

I shook my head yes.

“Which Lassù in cielo? I say it at least a dozen times or more.”

“PICK ONE MIDWAY THROUGH!”

The mix of confusion, fear, and helplessness on my face must have struck a chord because, for a fleeting moment, her steely exterior softened ever so slightly.

“Don’t worry. As we go, it will make more sense.”

(Please know I am using the M-word in this story to tell it the way it actually happened. In no way do I condone the use of it. I would like to acknowledge its use as inappropriate per the Little People of America’s Website.)

After she staged Caro Nome (the famous Act 1 aria for soprano), which basically consisted of me moving left to right a few times, her final instructions were that I “MUST go to the green mark center stage!” She insisted that there would be a green mark on the stage, and whatever I did, I had to finish lying down on that mark, and there would be men to get me.

“Yes”, she declared. “GO to the mark. Then, during the zitti zitti chorus, STAND UP, WALK over to the ladder, COME up halfway the ladder, and the men TAKE you.”

My face must have looked concerned.

“IT’S DEE KIDTNAPPING! JA?!”

(Spoiler. Gilda is kidnapped in the first act.)

“How tall is the ladder,” I asked.

Veins in her neck and forehead pulsed, and I swear she must have grit her teeth.

“It’s not TOO tall, but never mind. They know what to do. YOU BE THERE, AND THEY DO THE REST!”

She was clearly losing her patience, and I wanted this to be successful, so I decided to just sing my text, try to make the opera beautiful, and enjoy one of the most gorgeous operas ever written. My good-girl upbringing and American music school team-player attitude were pristine.

During our break, I learned I wasn’t alone in my uncertainty. My Duke—my character’s love interest—was a familiar face from the U.S., also making his debut with the company. He was visibly uneasy, and for good reason. In his opening aria, rather than commanding the stage with presence and staging action, he was expected to stand completely still and sing while acrobats tumbled, flipped, and twisted around him in a dizzying spectacle of gymnastic flair. This was not exactly the idea he had in mind to make his grand entrance for his European debut.

“I mean, I can act, you know?” I remember him saying.

“Did you hear her say I was in blackface?” I asked him quietly.

“Yeah. What the hell,” he said. “Don’t worry. There’s no way that’s correct,” he assured me.

We stumbled through the rest of the day as best we could, hitting all of her crucial marks: midget nun finger push, green mark end of Caro Nome, climb the ladder which in the rehearsal was mimed, all this while the conductor seemed to be reading the piece for the very first time, his head down in the music and unsure of every tempo and never giving room for the singers to breath. Tempi were either too fast or way too slow, and this music for the singers is crucial for collaborative listening, not just from the conductor but also to your fellow singers during duets. Some experience with Verdi would have been nice, but considering the other issues, we shrugged on, with no time to deal with anything other than a blueprint, and hoped for extra time to reveal itself so that we could perhaps make a little art at some point.

In three days, we put together what most would consider an outline for a production. The only difference was that we put it together to perform for the season's opening night at the Deutsche Oper. It was our product for what most consider to be one of the most exciting nights for a theater. All I could think was that it felt like carefully nurturing a rare, delicate vegetable—tending to it with rich soil, sunlight, and care—only to see it stripped of its essence, wrapped in plastic, and tossed onto a fluorescent-lit grocery store shelf.

Opening night arrived, and I had a lot of mixed feelings. I was very nervous. We had not run the show from beginning to end, we had only gone through the arias once with the conductor, and I had no idea what my staging was about. As I walked to my dressing room that night, all I could do was tell myself to perform the role as best as I could. Text first, staging second, trust the music and the fact that it was, after all, a Verdi masterpiece.

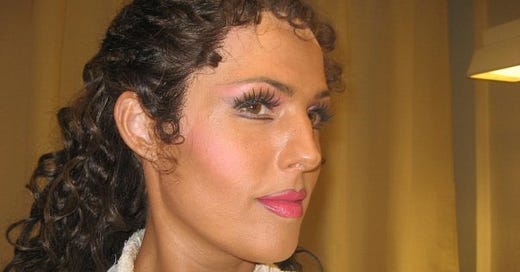

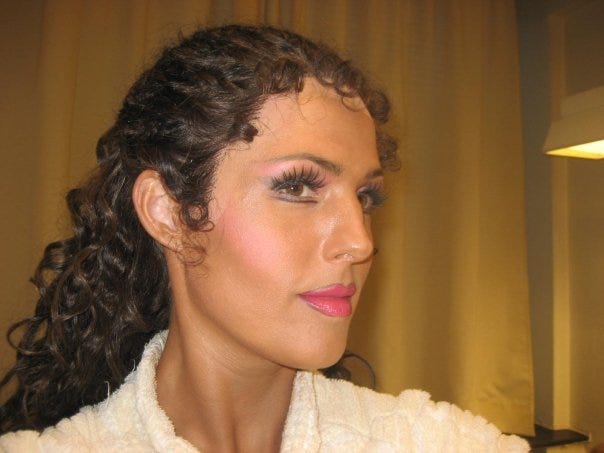

I walked down the long, dark hallway into my room to gird my loins for my German debut. I expected some flowers or opening night fanfare but instead, there, on the counter under the dressing room lights, was my wig, complete with cornrows and curls.

“Shit!”

I had shoved the thought of being in blackface to the back of my mind, clinging to the hope that, amidst the whirlwind of rehearsals, they might simply forget. What I hadn’t considered, however, was the wig. Seeing it in that cold hospital-like room, I felt a fresh wave of unease. It was long and dramatic, a style that could have suited an Eastern princess like Lakmé or Leïla. Thankfully—aside from the cornrows woven into its design—it didn’t immediately scream African caricature. But the implications still lingered.

I debated on what to do.

I remembered my Italian debut at the Carlo Felice in Genoa, Italy, where I performed Cunegonde in Candide. During the first dress rehearsal, Tichina Vaughn, the Old Lady in the production (actual character name), a Southerner like me, and an African American ran to my dressing room in horror. She drug me into the hallway, and there, to both our shock, stood the character Cacambo dressed exactly like Al Jolson, the darkest blackened face and the whitened mouth, complete with overalls, a red and white striped shirt, and white gloves.

I gasped.

Without hesitation, Tichina stormed off to speak with the administration in fluent Italian, passionately explaining the historical weight and deeply offensive nature of dressing the character in such a way. She tried to make them see that, as Americans, we simply couldn’t stomach the portrayal, but they were unmoved. Despite her best efforts, the costume remained for the entire run of the show. Every time I passed him in the hallway, that jarring image lingered—an uncomfortable reminder of how differently we interpreted certain symbols and how far from home I was.

I realized it was too late to convince the assistant director to alter the concept, but I wasn’t ready to surrender just yet. When the makeup artist arrived, my nerves were on edge, but I was relieved to see there wasn’t a pot of black pancake makeup on her cart. Instead, she had a range of brown and tan shades—though I worried it was still an insulting concept, I hoped the hot bright lights on my fair skin, would just make it all look as if I had a tan. I had just returned from Greece, after all.

I hesitated, then asked her not to darken me too much, explaining that I wasn’t comfortable with the idea. She agreed and confessed she never understood why they even attempted it, as it never really read as authentic. She blasted through the application, painting, brushing, and gluing on eyelashes. When she left, I looked in the mirror and realized she used a black eyeliner to line my lips with and had gone quite a bit out of the natural edge of my lips. Seeing how absurd the whole thing looked, I snapped a quick photo, then wiped it off and used my personal lipstick instead.

In the end, I looked more like a tanned version of myself—except for the wig. Some might have even mistaken me for Latina rather than the female Al Jolson caricature I had feared I'd be forced into. But whether they saw Latina or Black, I knew it was insensitive and maybe not wrong in Germany, but completely disgraceful back home.

It was the dawn of social media, so any public controversy passed me by. Still, I wish I had found the courage to refuse outright, to make a scene if necessary, to demand an end to this outdated and offensive practice. Or at the very least, to simply say no and walk away until the production aligned with my values. But I wasn’t there yet. I hadn’t fully grown into myself. That growth would take years—lying in the dirt on the MET stage, being called "fat" as an Amy Winehouse-inspired Violetta, and enduring countless moments of artistic doubt and compromise.

I wish I could say blackface, midget nuns with rubber fingers, and acrobats were all I had to contend with in the production, but the most devastating was yet to come.

As the opera began, an overwhelming sense of disconnect hit me—one I had never experienced on stage before. Nothing felt honest, and I couldn’t shake the feeling of being both awkward and inauthentic. Operatic emotion is already a delicate thing to convey. Often, it feels like wading the emotions through molasses, but when you’re trapped in a world straight out of a Game of Thrones novel, and every word you sing contradicts the very movements you make, any sense of grounded clarity evaporates. The artifice became suffocating, and I felt like I was drowning in a performance that wasn’t mine to begin with.

I made it to the duet with Rigoletto and managed to cue the child dressed as the small-person nun. To my surprise, the rubber finger didn’t garner any laughter from the audience. It was like they understood the concept and what was happening.

I got to Caro Nome, the big first-act aria, which was difficult and exposed, and it was something I’d been singing for nearly ten years at that point. The staging was almost nonexistent, and I felt myself moving back and forth almost apologetically, trying to make up for the lack of set pieces. At that moment, the stage was empty, and I was just supposed to sing. Everything was going well vocally. I was nervous and had a million things going on in my mind, but I was running through the motions of an aria I knew very well.

“Good Leah. Trill and release the body. Don’t reach for that note! Try to feel your feet. Ground yourself!”

“Find the green mark! It’s time for the green mark. DO NOT be late, she said!!!” I scolded myself.

I found it. Under the stage lights, it took on a more yellow hue. As I approached, I steadied myself for the long cadenza, the intricate melismatic passage that would close the piece. It began with a soaring high B natural, cascading down to a low D-sharp before a fleeting pause—barely a second to catch a breath. Then, the final stretch: a series of crisp, staccato notes climbing back up to the D-sharps. I had conquered this cadenza countless times—hundreds if not thousands—a familiar ritual.

But this time?

During the brief pause at the bottom of the scale, just as I prepared to take a breath and launch into the final flourish, a loud, off-key honk erupted from just offstage to my right. The timing was impeccable—almost too perfect, as if designed to rattle me. And it did. In that split second, whether from nerves, lack of rehearsal, sheer panic, or some strange out-of-body detachment, my focus shattered.

I took the breath—and botched the rest of the cadenza.

It was the strangest thing ever. I knew once I heard that note that it was wrong, but for some reason, in that nanosecond, my nerves shifted to the mysterious note instead of the one I’d rehearsed for a decade. I knew once I’d taken that breath that the next note was wrong, but I had started and couldn’t start again. Like I was hovering over myself trying to right it, I couldn’t and kept going and ended the aria, and when the orchestra entered, it was blatantly obvious I was off. I had been in a different key for that portion of the cadenza.

The horror.

“You are out of tune. Flat. Sharp. Who knows. Goddamn it.”

Then, to top my mortification, the German audience didn’t applaud.

Crickets.

I wasn’t sure if that was because I was so awful or because the conductor didn’t allow it; he just kept plowing on through the music.

But wait, there’s more.

I hit the green mark as commanded to do, lying there on center stage, with no applause, and there at the playout of the aria, a large plexiglass cylinder started to emerge from the stage flies or theatrical rigging system. I understood then the importance of being on the green mark. Had I not, I would have been cut into by this huge set piece.

“Ah, Gilda trapped in a glass jar. Jesus.” Me too, girl. Me too.

A ladder appeared, and I dutifully climbed to the halfway point, which was at least five feet high. Out of nowhere, the chorus men appeared dressed as frogs, something clearly lost in translation. They jumped around and danced to the beat of the music.

Zitti Zitti.

One frog leaped into the plexiglass jar with the speed and precision of an acrobat, snatched me up, and effortlessly flung me over the top, where another frog was already poised to catch and lower me down. It happened so fast and with such precision. I’ve often wondered how they managed it without us tumbling off into the orchestra pit. In normal circumstances, this would have been rehearsed ad nauseum, and a fight call would have been called before each performance to ensure safety.

From there, they lined up like a surreal assembly line, hurling me from one to the next in a dizzying display of coordination. My body trembled, but to my bewilderment, I found myself laughing uncontrollably—a reaction that now seems almost absurd. But in that moment, I was completely untethered, disoriented, lost in a whirlwind of movement and miscommunication. Nothing was in my control.

During intermission, I confronted the stage manager. I explained what I had heard off stage.

“It sounded as close as a flyman, ready to pull a piece of scenery!” I declared.

I demanded to know who sang a note off-stage during my aria. She impatiently said she didn’t know what I was talking about and had not heard anything. But I saw a few chorus guys and knew they knew what had happened. I could tell by the smirk and devilish look on their faces, holding back laughter, that they knew and that it had given them some pleasure that I had succumbed to someone’s off-stage antics.

We plowed on through the rest of the opera. My black face became lighter and lighter as it soaked into my skin, as my sweat wore it thin. I made it to the end, where I was to shimmy through a sheath of parachute-like cloth, what the director called the condom, which was to simulate the gutter Gilda is thrown into once she is stabbed.

(Apologies for all the spoilers.)

I got tangled in all the fabric and couldn’t do the shimmy work very well. It was to be inside out, then right side up once I snaked through. But, for me, it was like the twisted, tangled bed sheets you pull out of the dryer, and at that point, I was so tired, frustrated, and quite frankly embarrassed that I didn’t care what happened beyond that point.

Singing the final phrases, “Lassú in cielo” enmeshed in a web of sheets, all I wanted was to be transported out of that nightmare. I couldn’t stand on my own to clear the stage for the curtain calls because my legs were in a knot with my gown and the condom-parachute analogy. Hence, a rush of stage management had to come to lift me out along with the unending layers of fabric to the side stage, where the only solution was to undress and redress for the bows.

As the curtain fell, relief flooded over me—I couldn’t get out of my costume and makeup fast enough. There was no celebration, no lingering backstage chatter. I called my manager immediately, instructing him to contact the theater and withdraw me from the production. With no family or friends in attendance, I slipped away unnoticed, making my way back to my apartment, eager to put the night behind me, but wondering what I would do.

What had just happened? Would I ever be invited to sing at this company again?

But just as I was leaving the theater, I overheard a gut-wrenching piece of news from one of the supporting singers in the cast: Deutsche Grammophon, the most prestigious classical music recording label, had been in the audience. I wasn’t being scouted for a record deal, but that hardly softened the blow—of all nights for them to witness, it had to be this one. I cringed at their reaction, imagining their shock and disappointment at the disaster unfolding on stage. To make matters worse, there hadn’t been a shred of Verdi’s spirit coming from the conductor or the pit to salvage even a moment of redemption. My mind raced to my mentors—Virginia Zeani, Renata Scotto—women who had shaped my artistry. I winced, unable to bear the thought of what they would have said.

I tried to sleep. The next day, I paced around my apartment, unsure of what to do or how to move forward. I was so humiliated, angry, and frustrated. How did this happen to me? How could all this work I had poured into my singing start unraveling? What have I done wrong? I’m following all the rules! What was going on?

It seemed that the German regie nonsense had thrown me off my game and that I was also losing my way. Everything that had worked for me was no longer working. Could I not trust my voice? Wait, does practice makes perfect not work? Am I supposed to like this? Being on stage was starting to feel less like elevated art and more like juggling in a circus in a routine I couldn’t nail down.

I was standing on shaky ground. More performances loomed ahead, and in just four days, I was scheduled to fly to Arizona to begin rehearsals for another production of the same role—only to turn around and fly back to Germany to finish my final shows in Berlin. As I stared at my packed schedule, the weight of it all bore down on me. I had already been away from home for months, and something inside me began to crack.

I needed a break.

For five years, I had been moving at full speed—building my career, losing the voice teacher I had relied on for a decade, going through a divorce, starting a new relationship, buying a house, relocating to Atlanta, and somehow keeping an international singing career afloat. How many hundreds of pages of music had I memorized in that time? The mere thought of the grueling journey from Berlin to Phoenix made me dizzy. The jet lag, the exhaustion, the expectation to perform at full capacity when my voice and spirit felt utterly depleted—it was too much to fathom. Desperate, I searched for a flight home the next day.

The cost?

$2,500.

There was no quick escape.

The next day, the intendant, the opera company manager, called to discuss my wanting to leave the production. He insisted that my performance was stellar and that I shouldn’t worry about what I felt or what happened in Caro Nome because “German audiences don’t always applaud.” He was personally very pleased with the performance and wanted me to continue. I was actually very shocked that he didn’t purchase my flight home himself.

Feeling somewhat reassured, I decided to stay but asked for more rehearsal time before the next performance. It turns out the tenor was feeling the same way. So they called for a rehearsal the next day to iron out stage issues and set more tempi with the conductor. It also came to the surface that some of the orchestra members didn’t like and respect the conductor, so they were making his life hell in the pit, which was more hell for us, and explained why nothing was responsive from the pit opening night.

We spent another day desperately trying to make sense of the staging. I focused on grounding myself in the music, determined to bring clarity and intention to my musical phrases. After all, I had studied this role under the greatest Italian divas—women directly connected to Verdi himself (and perhaps even God). Yet here I was, led by a conductor who was rigid and unresponsive. He was suffering his own sort of career demise.

This stumble was more than I could bear—for someone so obsessed with perfection, failure wasn’t an option. And yes, I took this to be failure.

Singing out of tune? Quelle horreur!

I took full responsibility. I had felt my singing shifting. At 33, I had switched voice teachers, but with the sheer amount of music I’d had to learn over the past two years, I never had time to truly settle in and work with someone new on a consistent basis. I was figuring it all out on my own, and honestly, I was proud of that. I coached with pianists to check accuracy and diction, but technically, I was flying solo—and for the most part, it worked.

So instead of stepping back and seeing the bigger picture—the impossible circumstances, the lack of rehearsal, the chaos—I turned on myself. I convinced myself that I should have been unshakable, no matter what. That I should have triumphed despite it all. It was a toxic expectation, one that would come back to crumble me a few years later with Madness at the MET.

In my journal from that time, I wrote:

I had a dreadful opening night as Gilda. For many reasons, the production was a nightmare, so much out of my control. Eurotrash opera at its worst. Gilda in black face, cornrows, because Harolyn Blackwell had originated the production. I'm assuming most of this explanation was lost in translation, but I agreed to the blackface, to my horror. It was all so last minute.

A "midget" nun with a large plastic rubber finger, men dressed as frogs to "rape" Gilda, and a tunnel meant to simulate a condom instead of a sewer as she dies in the end. Nightmare.

A mocking of Verdi and his sentimental music and extraordinary opera.

I could go on and on about how that didn't help me do my best, how it got in my way, and how opening night, all kinds of new things were thrown at me. Having three days to mount this was not enough time, especially with a conductor who had never conducted the opera before.

The worst was that my cadenza in Caro Nome was a disaster. I don't know what happened, but I heard someone in the chorus of men off stage hum or bow or shout a pitch that was not even close to the key of Caro Nome right as I went to sing the high b and make the descending cadenza followed by the high staccati pitches. I ended it in the wrong key, and there was no applause.

The chorus of frogmen came to pick me up and carry me off, singing "Zitti Zitti," and I was shaking.

I've sung this cadenza a million or so times. It came completely out of tune.

I know with all my heart that someone intended to throw me off, even though stage management says I'm imagining it.

I'm so angry that it worked. Aren't I a better singer? I should have been like a rock on stage.

I've never had problems with the cadenza before.

Afterward, I spoke with my manager and told him to call the intendant and suggest I withdraw from the production. The next day, the intendant called me and insisted that I stay and offered me a few more rehearsals to iron out more details with the conductor and in my duets.

So I've stayed. I completed the contract, but I feel quite certain that I'll never be asked back.

My second performance was quite better than the first. The cadenza still wasn't where it was a few years ago. In tune, but scary. The rest of the opera was okay. Actually, there were some moments I had some really nice sounds. Of course, everyone tells me that it wasn't as bad as I think.

I know that it isn't my work though. I don't want to sing like this. I don't want to be an insecure singer.

I've canceled my Gilda's in Arizona. It was double cast anyway, and a young soprano, Lisette Oropesa, can have them all for all I care. I was supposed to fly back to Phoenix between these performances to start rehearsals. I can't do it. It's too much. The flights alone will make me so tired, and my voice isn't working as it should. I'm letting so many people down.

At least I have a month off and I can practice. Perhaps I haven't completely ruined my career. It may take some time for me to feel confident but I know what is important and it is to work hard and slow down. I have to say no more and I have to work out a schedule that will allow me to get some study and home time in. But, I always need the money. I have bills to pay.

I've never wanted a time to be over faster in all of my life. When my last notes were sung last night, I had a huge relief in my heart. I thought, I never have to sing this opera again if I don't want to, and it felt amazing to know that I'm starting to learn to say no.

Reading this old journal entry, a few things hit me hard. First, I was always busy—so busy that I genuinely believed constant motion was the secret to building a stellar career. Second, learning so much music back-to-back, entirely on my own, was draining me more than I realized. Third, despite working non-stop, money was still a worry, so I said yes to absolutely everything, afraid that turning down a single gig might derail everything I’d built.

But the biggest realization? I took full responsibility for every setback—every flaw, every failure, every moment my voice or career didn’t progress exactly as I’d hoped. I saw them as personal shortcomings, as proof that I wasn’t enough, and I shamed myself relentlessly for years. I never stopped to consider how losing a longtime teacher, getting poor guidance from a manager, or simply wearing my overachiever badge with pride was slowly grinding me down and separating me from a good supportive team. I thought I was following the blueprint for success, doing everything I had been taught. And in many ways, I was succeeding. I was working, and in an industry as brutally competitive as opera, that alone was a victory. But at what cost?

Was I making art?

Was I doing something that was lasting and compelling?

One’s voice has a way of exposing exactly what’s going on inside. The mind and nervous system are intricately tied to it—it is the instrument, and the sounds you produce are just the result. So when you’re stressed, sad, or overstimulated, you feel it in your voice. And for those of us who train our voices with the same precision and intensity as top athletes, those shifts aren’t subtle; they hit like a tidal wave.

Sure, we might still be performing at a high level, pushing through the endless stressors that come with this career. But when our system is overloaded, we don’t always have the bandwidth to make the fine-tuned technical adjustments our voices require.

For example, after a decade of singing a cadenza, one note can derail us because it isn’t just the note that is interrupting our brain. It was a combination of loss, insecurity, unrehearsed staging, high stakes, and newness, causing the override of what I normally did. While it is very tempting to claim yourself as bulletproof, everyone has a threshold of where their capacity for this amount of stressors will cause a bauble if not a bursting of the bubble. And it’s proven that when one is in a fight or flight state or feeling unsafe or insecure, that intonation will suffer. Imagine what slight adjustments you make in your singing instrument to get the notes just right in a cadenza like Gilda’s. Then, imagine doing this in a high-stress situation. Even the slightest variation in your posture can threaten the accuracy and overtones. It should be no surprise that this chorister was able to derail my cadenza.

I’ve also come to realize that while being in demand as a singer can feel exhilarating—racing around the world to keep up with a packed schedule, feeling important, feeling wanted—it comes with a cost. The pressure to make it all happen quickly can be overwhelming, and asking for what you truly need can feel uncomfortable or even unwelcome. Sometimes, you may not even know what you need.

That’s why it’s crucial to pay close attention to your energy and emotional state when performing and making big decisions. Since our nervous system is the true instrument behind our voices, learning to recognize its natural fluctuations can reveal just how often we’re performing under strain. And if self-awareness feels out of reach alone, there are now plenty of workshops designed to help singers and artists identify these patterns—because understanding your body is just as important as perfecting your technique.

I’ve personally gained so much from Ruby Rose Fox’s work at Muscle Music. She teaches performers how to “unshame the nervous system,” helping us understand that the shifts we feel—whether it’s anxiety, tension, or discomfort—aren’t wrong or unnatural. Instead of fighting against them, we learn to navigate them, making it easier to find a state of ease and confidence.

This work is powerful because it reminds us that our nervous system isn’t the enemy—it’s designed to protect us from danger and stress. And once we understand that, we can start to build resilience for the awkward moments: the rough rehearsals, the unexpected mishaps on stage, the pressure of high-stakes performances. More importantly, we learn to advocate for what we need, because we’ve established a system that actually works for us.

When we, as performers, lead from a regulated state—without the telltale signs of distress like darting eyes, shallow breath, or rigid movement—we create a ripple effect. We’re not just more grounded in our own artistry; we also guide our audiences into that same space. And that’s where the magic happens—when we can fully express ourselves, even in the most painful or intense emotions, without resistance. Because when we feel at ease, our audiences feel it, too.

I'm not saying it should be easy—because that's where the growth happens. The challenge of mastering your craft isn’t the problem. What truly matters is learning to navigate it when it arises and standing up for yourself amid a plague of Frogs, Gilda-like cadenzas, and German Regie theater.

Holy. Shit. What an INSANE situation🤯🤯🤯